Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Assessing Alternatives To Toxic Chemicals

Governments, businesses, and now the National Academy of Sciences consider how to avoid 'regrettable substitution'

by Cheryl Hogue

December 16, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 50

Eliminating a toxic substance from a product’s ingredients seems like a straightforward way to improve product safety. But when a toxic chemical gets removed from a product, some other substance—or substances—goes in as a replacement to carry out that ingredient’s function, such as softening plastic or helping remove grease. Such a switch is intended to resolve the problem. But in some cases this situation can lead to what is being called “regrettable substitution.”

For example, brake cleaner, which auto mechanics use, once contained chlorinated solvents, primarily methylene chloride. But in the 1990s, pollution control regulations pushed manufacturers of the cleaner to rid their products of chlorinated solvents. In place of these compounds, brake cleaner makers substituted n-hexane, which performs well in their products.

By the late 1990s, physicians began to report that auto mechanics using brake cleaner were suffering nerve damage, according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Since the 1960s, n-hexane has been known to be neurotoxic. Product makers had swapped chemicals with a significant pollution downside for a substance that posed a serious health risk to workers.

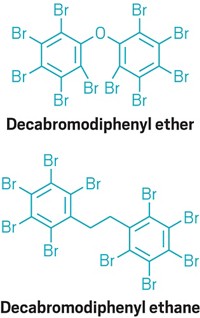

More examples exist as well. Regulations and other policies around the world are restricting the use of polybrominated diphenyl ethers. This class of once widely used flame retardants has been found in people, wildlife, and the environment and is linked to toxicity in experiments with laboratory animals. Companies manufacturing products that must meet flammability standards are switching to other flame-retardant chemicals that are technically and economically feasible. Yet some of the substitutes may also be toxic.

Given the need to weigh trade-offs, interest is burgeoning in assessments of chemicals that can substitute for more toxic substances.

Governments are busy in this area. The Environmental Protection Agency earlier this year drafted an assessment of chemical alternatives to hexabromocyclododecane, a persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic flame retardant used in polystyrene insulation. California is wrestling with the evaluation of alternatives as it implements the first regulatory effort in the U.S. pushing consumer product makers to shift from the use of hazardous chemicals to safer ingredients (C&EN, Oct. 7, page 13). A coalition of regulatory agencies from 11 states is finalizing guidance for alternatives assessment. And internationally, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation & Development—a group of 34 of the world’s richest countries—is working to harmonize practices among its members on what it calls substitution of harmful chemicals.

As corporate customers and consumers alike increasingly demand elimination of toxic chemicals from products, companies are joining ranks with others to tackle alternatives assessment.

BizNGO, a group of leaders from business, government, academic, and environmental groups, in October released principles to guide retailers and product manufacturers in assessing alternatives and avoiding regrettable substitution. And the Green Chemistry & Commerce Council, an organization of chemical manufacturers, product makers, and retailers, recently released a report identifying and assessing nine plasticizers that could serve as alternatives to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) in coatings for wire and cable. The European Union is phasing out DEHP under its Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation & Restriction of Chemical substances law because of concerns about adverse health effects.

Now, the National Academy of Sciences is bringing its expertise to bear on the issue. At the behest of EPA, the NAS Board on Chemical Sciences & Technology is studying design and evaluation of safer chemical substitutions. The committee preparing the report held a public meeting in November to garner input.

Alternatives assessments voluntarily conducted by the private sector will play a key role in improving safety of commercial chemicals in years to come, said James J. Jones, assistant administrator of EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety & Pollution Prevention. That’s because regulatory processes for controlling commercial chemicals can take years to implement, he told the committee.

Gina Solomon, deputy secretary for science and health at the California Environmental Protection Agency, urged the panel to consider technology changes—and not just substitution of one chemical for another. Assessments that take into account process changes to reduce use of hazardous chemicals can create additional opportunities for green chemistry and green engineering solutions, she said.

Solomon also challenged the committee to address assessments done for alternative chemicals for which little or no toxicity data exist. Jones noted that an overwhelming majority of chemicals on the market now have never undergone safety assessments.

In contrast, chemicals targeted for substitution because of the risks they pose are often well-studied compounds, commented NAS committee chairman David C. Dorman, a professor of toxicology at North Carolina State University.

The goal of alternatives assessment should be to maximize net benefits of chemicals to society, said Michael P. Walls, vice president of regulatory and technical affairs at the American Chemistry Council, an association of chemical manufacturers. Exposure information is essential to ensure this goal is met, he asserted. Assessments should evaluate exposure to that compound during each step of a product’s life cycle, from manufacturing through use and recycling or disposal, he said.

But exposure information for many chemicals is sparse, and exposure to a chemical can increase or decrease over time, countered Jennifer McPartland, health scientist for the Environmental Defense Fund, an activist group. Because a compound’s hazardous properties do not change, switching to a safer substance can help society by obviating a disaster, she told the panel.

The committee’s report, which will be aimed at helping industry and governments evaluate alternatives, is expected to be completed in 2014.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter